U.S.A.A.F. RESOURCE CENTER > BOMBERS > FLYING FORTRESS > PREVIOUS PAGE

Operational History

Early models proved to be unsuitable for combat use over Europe and it was the B-17E that was first successfully used by the USAAF. The defense expected from bombers operating in close formation alone did not prove effective and the bombers needed fighter escorts to operate successfully.

During World War II, the B-17 equipped 32 overseas combat groups, inventory peaking in August 1944 at 4,574 USAAF aircraft worldwide. B-17s dropped 640,036 short tons (580,631 metric tons) of bombs on European targets (compared to 452,508 short tons (410,508 metric tons) dropped by the Liberator and 463,544 short tons (420,520 metric tons) dropped by all other U.S. aircraft). The British heavy bombers, the Avro Lancaster and Handley Page Halifax, dropped 608,612 long tons (681,645 short tons) and 224,207 long tons (251,112 short tons) respectively.

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force entered World War II with no heavy bomber of its own in service; the biggest available were long-range medium bombers such as the Vickers Wellington which could carry up to 4,500 pounds (2,000 kg) of bombs. While the Short Stirling and Handley Page Halifax would become its primary bombers by 1941, in early 1940 the RAF entered into an agreement with the U.S. Army Air Corps to be provided with 20 B-17Cs, which were given the service name Fortress I. Their first operation, against Wilhelmshaven on 8 July 1941 was unsuccessful; on 24 July, the target was the Scharnhorst, anchored in Brest. Considerable damage was inflicted on the vessel.

Royal Air Force Fortress I.

[Source: RAF Photo]

As usage by Bomber Command had been curtailed, the RAF transferred its remaining Fortress I aircraft to Coastal Command for use as a long-range maritime patrol aircraft instead. These were later augmented in August 1942 by 19 Fortress Mk II (B-17F) and 45 Fortress Mk IIA (B-17E). A Fortress from No. 206 Squadron RAF sank U-627 on 27 October 1942, the first of 11 U-boat kills credited to RAF Fortress bombers during the war.

The RAF's No. 223 Squadron, as part of 100 Group, operated a number of Fortresses equipped with an electronic warfare system known as "Airborne Cigar" (ABC). This was operated by German–speaking radio operators who would identify and jam German ground controllers' broadcasts to their nightfighters. They could also pose as ground controllers themselves with the intention of steering nightfighters away from the bomber streams.

Initial USAAF operations over Europe

The air corps (renamed United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) on 20 June 1941), using the B-17 and other bombers, bombed from high altitudes using the then-secret Norden bombsight, known as the "Blue Ox", which was an optical electro-mechanical gyro-stabilized analog computer. The device was able to determine, from variables input by the bombardier, the point at which the aircraft's bombs should be released to hit the target. The bombardier essentially took over flight control of the aircraft during the bomb run, maintaining a level altitude during the final moments before release.

B-17 Flying Fortress formation.

[Source: USAF Photo]

Two additional groups arrived in England at the same time, bringing with them the first B-17Fs, which would serve as the primary AAF heavy bomber fighting the Germans until September 1943. As the raids of the American bombing campaign grew in numbers and frequency, German interception efforts grew in strength (such as during the attempted bombing of Kiel on 13 June 1943), such that unescorted bombing missions came to be discouraged.

Combined Day/Night operations

The two different strategies of the American and British bomber commands were organized at the Casablanca Conference in January 1943. The resulting "Combined Bomber Offensive" would weaken the Wehrmacht, destroy German morale and establish air superiority through Operation Pointblank's destruction of German fighter strength in preparation for a ground offensive. The USAAF bombers would attack by day, with British operations – chiefly against industrial cities – by night.

Operation Pointblank opened with attacks on targets in Western Europe. General Ira C. Eaker and the Eighth Air Force placed highest priority on attacks on the German aircraft industry, especially fighter assembly plants, engine factories and ball-bearing manufacturers. Attacks began in April 1943 on heavily fortified key industrial plants in Bremen and Recklinghausen.

Since the airfield bombings were not appreciably reducing German fighter strength, additional B-17 groups were formed, and Eaker ordered major missions deeper into Germany against important industrial targets. The 8th Air Force then targeted the ball-bearing factories in Schweinfurt, hoping to cripple the war effort there. The first raid on 17 August 1943 did not result in critical damage to the factories, with the 230 attacking B-17s being intercepted by an estimated 300 Luftwaffe fighters. The Germans shot down 36 aircraft with the loss of 200 men, and coupled with a raid earlier in the day against Regensburg, a total of 60 B-17s were lost that day.

A second attempt on Schweinfurt on 14 October 1943 would later come to be known as "Black Thursday". While the attack was successful at disrupting the entire works, severely curtailing work there for the remainder of the war, it was at an extreme cost. Of the 291 attacking Fortresses, 60 were shot down over Germany, five crashed on approach to Britain, and 12 more were scrapped due to damage – a total loss of 77 B-17s. A total of 122 bombers were damaged and needed repairs before their next flight. Out of 2,900 men in the crews, about 650 men did not return, although some survived as prisoners of war. Only 33 bombers landed without damage. These losses were a result of concentrated attacks by over 300 German fighters.

Such high losses of aircrews could not be sustained, and the USAAF, recognizing the vulnerability of heavy bombers to interceptors when operating alone, suspended daylight bomber raids deep into Germany until the development of an escort fighter that could protect the bombers all the way from the United Kingdom to Germany and back. At the same time, the German night fighting ability noticeably improved to counter the nighttime strikes, challenging the conventional faith in the cover of darkness. The Eighth Air Force alone lost 176 bombers in October 1943, and was to suffer similar casualties on 11 January 1944 on missions to Oschersleben, Halberstadt and Brunswick. Lieutenant General James Doolittle, commander of the Eighth, had ordered the second Schweinfurt mission to be cancelled as the weather deteriorated, but the lead units had already entered hostile air space and continued with the mission. Most of the escorts turned back or missed the rendezvous, and as a result 60 B-17s were destroyed. A third raid on Schweinfurt on 24 February 1944 highlighted what came to be known as "Big Week", during which the bombing missions were directed against German aircraft production. German fighters would have to respond, and the North American P-51 Mustang and Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighters (equipped with improved drop tanks to extend their range) accompanying the American heavies all the way to and from the targets would engage them. The escort fighters reduced the loss rate to below seven percent, with only 247 B-17s lost in 3,500 sorties while taking part in the Big Week raids.

By September 1944, 27 of the 42 bomb groups of the Eighth Air Force and six of the 21 groups of the Fifteenth Air Force used B-17s. Losses to flak continued to take a high toll of heavy bombers through 1944 but the war in Europe was being won by the allies and by 27 April 1945 (two days after the last heavy bombing mission in Europe), the rate of aircraft loss was so low that replacement aircraft were no longer arriving and the number of bombers per bomb group was reduced. The Combined Bomber Offensive was effectively complete.

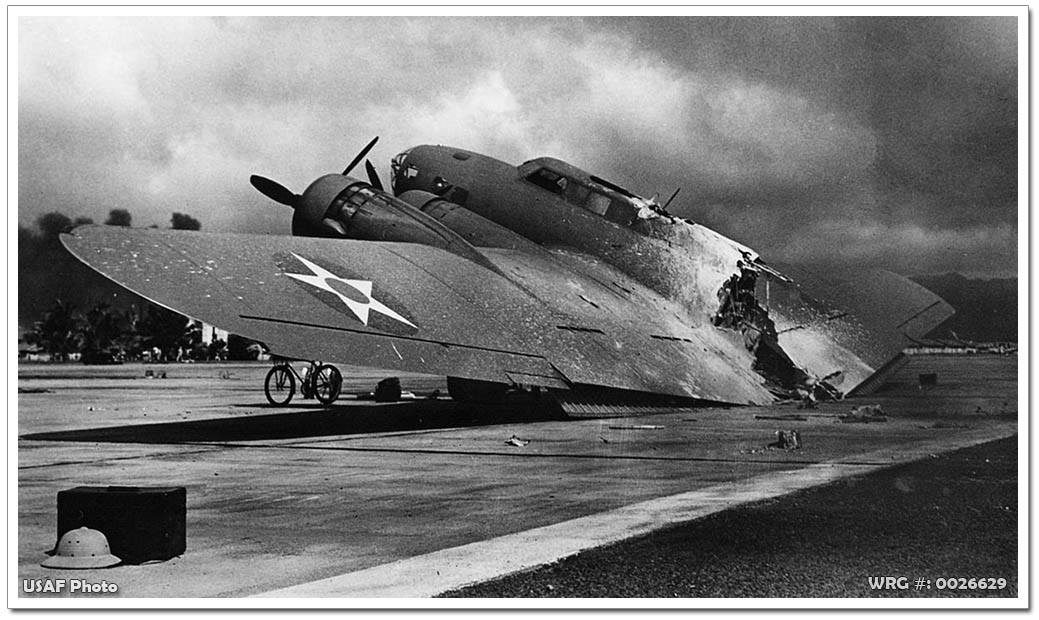

On 7 December 1941, a group of 12 B-17s of the 38th (four B-17C) and 88th (eight B-17E) Reconnaissance Squadrons, en route to reinforce the Philippines, were flown into Pearl Harbor from Hamilton Field, California, arriving during the attack on Pearl Harbor. Leonard "Smitty" Smith Humiston, co-pilot on First Lieutenant Robert H. Richards' B-17C, AAF S/N 40-2049, reported that he thought the U.S. Navy was giving the flight a 21-gun salute to celebrate the arrival of the bombers, after which he realized that Pearl Harbor was under attack. The Fortress came under fire from Japanese fighter aircraft, though the crew was unharmed with the exception of one member who suffered an abrasion on his hand. Enemy activity forced an abort from Hickam Field to Bellows Field, where the aircraft overran the runway and into a ditch where it was then strafed. Although initially deemed repairable, 40-2049 (11th BG / 38th RS) received more than 200 bullet holes and never flew again. Ten of the 12 Fortresses survived the attack.

Boeing B-17C Flying Fortress/40-2074 near Hangar 5,

at Hickam Field, Oahu, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941.

[Source: USAF Photo]

Another early World War II Pacific engagement on 10 December 1941 involved Colin Kelly who reportedly crashed his B-17 into the Japanese battleship Haruna, which was later acknowledged as a near bomb miss on the heavy cruiser Ashigara. Nonetheless, this deed made him a celebrated war hero. Kelly's B-17C AAF S/N 40-2045 (19th BG / 30th BS) crashed about 6 mi (10 km) from Clark Field after he held the burning Fortress steady long enough for the surviving crew to bail out. Kelly was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Noted Japanese ace Saburo Sakai is credited with this kill, and in the process, came to respect the ability of the Fortress to absorb punishment.

B-17s were used in early battles of the Pacific with little success, notably the Battle of Coral Sea and Battle of Midway. While there, the Fifth Air Force B-17s were tasked with disrupting the Japanese sea lanes. Air Corps doctrine dictated bombing runs from high altitude, but it was soon discovered that only one percent of their bombs hit targets. However, B-17s were operating at heights too great for most A6M Zero fighters to reach, and the B-17's heavy gun armament was more than a match for lightly protected Japanese aircraft.

On 2 March 1943, six B-17s of the 64th Squadron attacked a major Japanese troop convoy from 10,000 ft (3 km) during the early stages of the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, off New Guinea, using skip bombing to sink three merchant ships including the Kyokusei Maru. A B-17 was shot down by a New Britain-based A6M Zero, whose pilot then machine-gunned some of the B-17 crew members as they descended in parachutes and attacked others in the water after they landed. Later, 13 B-17s bombed the convoy from medium altitude, causing the ships to disperse and prolonging the journey. The convoy was subsequently all but destroyed by a combination of low level strafing runs by Royal Australian Air Force Beaufighters, and skip bombing by USAAF North American B-25 Mitchells at 100 ft (30 m), while B-17s claimed five hits from higher altitudes.

A peak of 168 B-17 bombers were in the Pacific theater in September 1942, with all groups converting to other types by mid-1943. In mid-1942, Gen. Arnold decided that the B-17 was inadequate for the kind of operations required in the Pacific and made plans to replace all of the B-17s in the theater with B-24s as soon as they became available. Although the conversion was not complete until mid-1943, B-17 combat operations in the Pacific theater came to an end after a little over a year. Surviving aircraft were reassigned to the 54th Troop Carrier Wing's special airdrop section, and were used to drop supplies to ground forces operating in close contact with the enemy. Special airdrop B-17s supported Australian commandos operating near the Japanese stronghold at Rabaul, which had been the primary B-17 target in 1942 and early 1943.

Sources:

Gunston, Bill - The Encyclodepia of the Worlds Combat aircraft, 1976, Chartwell Books, Inc., New York

Wikipedia

U.S.A.A.F. RESOURCE CENTER > BOMBERS > FLYING FORTRESS > PREVIOUS PAGE